2022-Apr-05

Anglers are Vulnerable to Tick Bites

As an angler I’m often treading along river shorelines or walking in tall grass and bushes. Nagging me, is the possibility that I may pass a shrub with a hungry tick waiting and then biting me, and I may not even know it! As ticks are most active in the spring and summer, an unwary angler could be their next target.

The Culprit and Where They Are Found

Hungry deer tick and engorged deer tick

Black-legged ticks (Ixodes scapularis), also know as deer ticks, are most often carried by deer and by migratory birds and are usually found in wooded areas or, in tall grasses, bushes and shrubs. Some of these ticks carry the bacteria which causes Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi) and a bite from such a tick causes the disease in humans.

In 2020 black-legged ticks were observed in Southeastern Georgian Bay as shown on the Public Health Ontario’s Lyme Disease Map . More recently, ticks have reached further north as reported by the North Bay Parry Sound District Health Unit advising caution as an increase in Lyme disease has been detected in their district.

Between April and July 2021, there have been two confirmed and two probable cases of Lyme disease with individuals residing in the district. Of 84 ticks submitted to the health unit for identification and testing for Lyme disease, 29 were identified as black-legged ticks or deer ticks and four tested positive for the bacteria causing Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi).

What are the Symptoms:

Most symptoms usually appear between three and 30 days after a bite from an infected blacklegged tick. When  fishing where ticks might live, you may experience one or more of the following symptoms: a bull’s-eye rash on the

fishing where ticks might live, you may experience one or more of the following symptoms: a bull’s-eye rash on the  skin often round or oval and more than 5 cm that spreads outwards. The other is a bruise-like rash. With any of these showing or any other unusual rash you should contact your local public health unit or speak to a health care professional right away. Other symptoms may include fever, chills, headache, stiff neck, muscle aches and joint pains or fatigue, swollen lymph nodes, spasms, numbness or tingling and facial paralysis. Symptoms from untreated Lyme disease can last years and include recurring arthritis and neurological problems, numbness, paralysis and, in very rare cases, death. The good news is that in most cases, Lyme disease can be treated successfully with antibiotics.

skin often round or oval and more than 5 cm that spreads outwards. The other is a bruise-like rash. With any of these showing or any other unusual rash you should contact your local public health unit or speak to a health care professional right away. Other symptoms may include fever, chills, headache, stiff neck, muscle aches and joint pains or fatigue, swollen lymph nodes, spasms, numbness or tingling and facial paralysis. Symptoms from untreated Lyme disease can last years and include recurring arthritis and neurological problems, numbness, paralysis and, in very rare cases, death. The good news is that in most cases, Lyme disease can be treated successfully with antibiotics.

How you can prevent a tick bite:

Prior to setting out along a wooded path or fishing along the banks of a river the following precautions should be taken:

- Wear light coloured clothing as it’s easier to see ticks. Wear long-sleeved shirts and tuck pants (avoid shorts) into your socks.

- Apply bug spray or other insect repellents that contain DEET (or Icaridin) on exposed skin and always read the label on how to use it (anglers should avoid getting repellent on their flies or lures).

- Throughout the day while visiting streams and walking on wooded paths, periodically check clothes, head gear and body for ticks, paying attention to the scalp and behind the ears.

- Wherever possible try to remain on cleared paths.

- Arriving home, kill any ticks that might be on your clothing using a dryer on high heat for at least 10 minutes prior to washing them. A shower is also recommended as soon as possible to wash off any ticks.

How to remove a tick:

- Removing a tick is the same for humans and animals. Check your pets’ skin and remove any ticks you find.

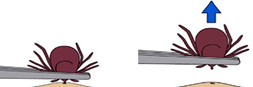

- Use fine-tipped tweezers and grasp the tick as close to your skin as possible but don’t squeeze as you might crush or damage the tick and this could cause Lyme bacteria to pass from the tick into your bloodstream.

Pull the tick straight out, gently but firmly and don’t jerk or twist the tweezers (Don’t use a lit match or cigarette, nail polish or nail polish remover or kerosene to remove the tick).

Pull the tick straight out, gently but firmly and don’t jerk or twist the tweezers (Don’t use a lit match or cigarette, nail polish or nail polish remover or kerosene to remove the tick).- Once the tick is removed, wash the skin with soap and water and then disinfect your skin and hands with rubbing alcohol or an iodine swab.

- If possible, place the tick in a bottle with a screw top so it can’t get out or be crushed and contact your local public health unit .

Source: Much of the information above and diagrams are from the Ontario Government’s web site www.ontario.ca/lyme.

Article by Bill Steiss, Chair GBA Fisheries Committee